“…during the Second World War, the Japanese government would not allow Koreans to publicly use Korean names. My brothers told me it was because they were trying to take away our language and, subsequently, our culture…” – Tomiko Lee, A Girl from Busan – pg 11

During World War 2, the Japanese banned Korean families from using their Korean names in an attempt to assimilate their culture and eventually erase it altogether. They also forced Koreans to worship at Japanese shrines, learn the Japanese language and history, as well as force thousands of women into sexual slavery and men to work in dangerous coal mines. But this attempt at obliterating the Korean culture began long before the World Wars took place.

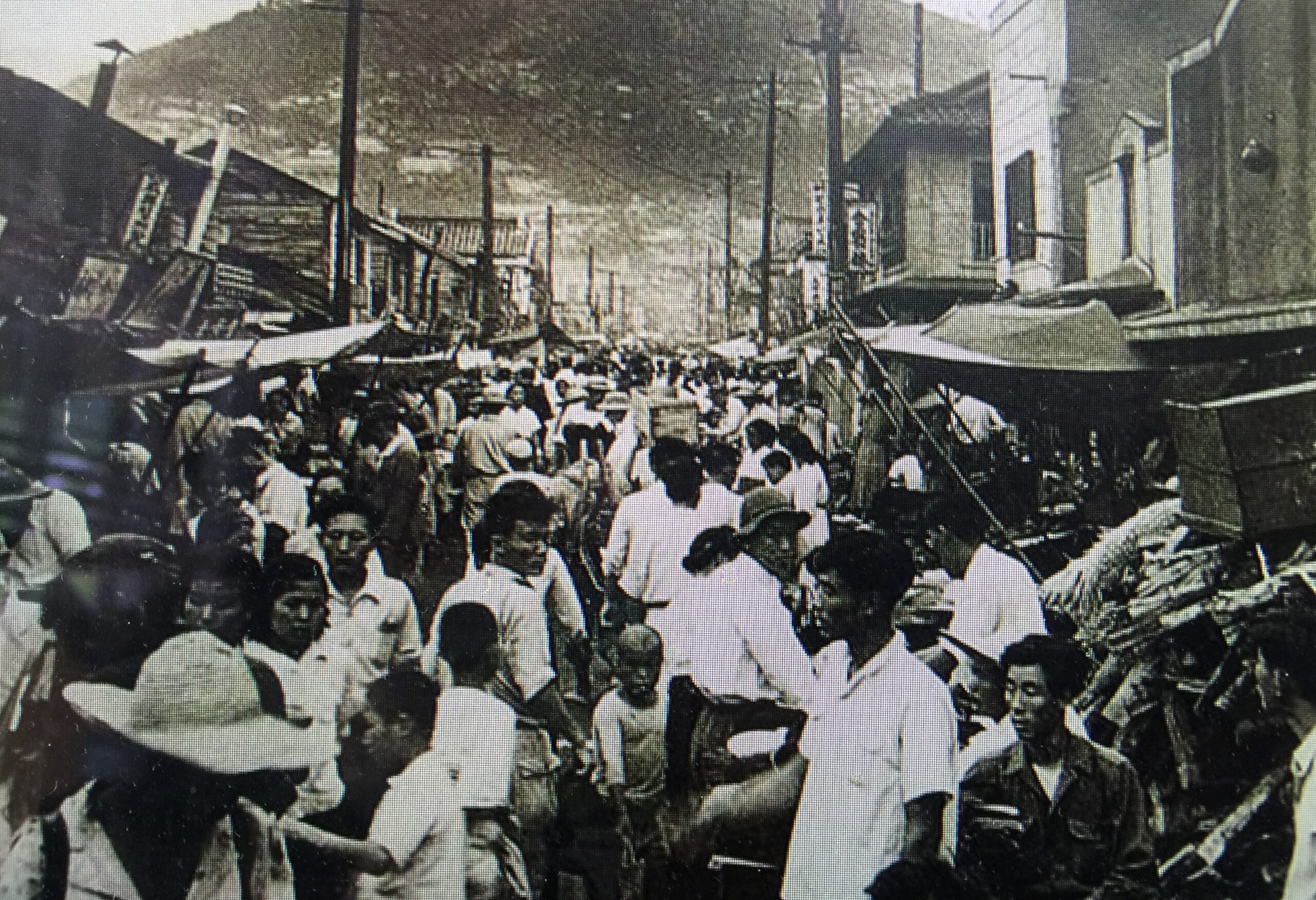

After the Russo-Japanese War (1904 – 1905), the Korean army was disbanded and the country’s long line of rulers and culture overthrown. Koreans were banned from publishing their own newsletters or taking part politically. This was both humiliating and afflicting to the people of Korea, so in an attempt of non-violent retaliation, thousands led a peaceful protest known as the First March Movement on March 1st, 1919. Japan responded in violence, killing over 7,000 Koreans. This was unfortunately only the beginning of over thirty painful years filled with Korean suffering under the rule of Japan.

For many years, Korea was used by Japan for its resources. New roads, power plants, hospitals and schools were built; and while these new things were beneficial to some, to many starving Korean families they were created for Japan’s best interests. Farmland belonging to clans were taken and sold cheaply to Japanese families, forcing homeless Koreans to find new homes and work elsewhere. Many left their homeland to find better opportunities in Japan.

By 1939, Koreans were shamed into taking on Japanese names. If one refused to do so, they were heavily persecuted by both government and by their new foreign neighbors. Some fought against the assimilation, but many were pressured to surrender the family name and take on new ones. Furthermore, Koreans were forced to worship in Shinto shrines; a disgrace to both the culture and the families by the highest degree.

Korea had been stripped, its people stolen, and its culture nigh erased. And yet, in the year 1945, on August 15th, Japan called for the Imperial Surrender – Korea was free! Many hopeful people fled to nearby train stations for the return trip home while many more began the long and arduous journey of restoring the Korean culture.

“…Nagoya Station was packed with people shouting, pushing, and shoving from every direction to board their train. We were surrounded by many Korean expatriates who were excited to share in the hope of a bright new future by returning to the motherland. Though I was only three years old and much too young to remember the journey, my older brothers and sisters would talk about our adventurous trip in the years to come…” – Tomiko Lee, A Girl from Busan – pg 13

“…Nagoya Station was packed with people shouting, pushing, and shoving from every direction to board their train. We were surrounded by many Korean expatriates who were excited to share in the hope of a bright new future by returning to the motherland. Though I was only three years old and much too young to remember the journey, my older brothers and sisters would talk about our adventurous trip in the years to come…” – Tomiko Lee, A Girl from Busan – pg 13